On Monday March 2nd the Landmark Commission voted to begin the initiation process to designate the Clyde Barrow Family Home and Filling Station (1221 Singleton Blvd) as an official City of Dallas Landmark.

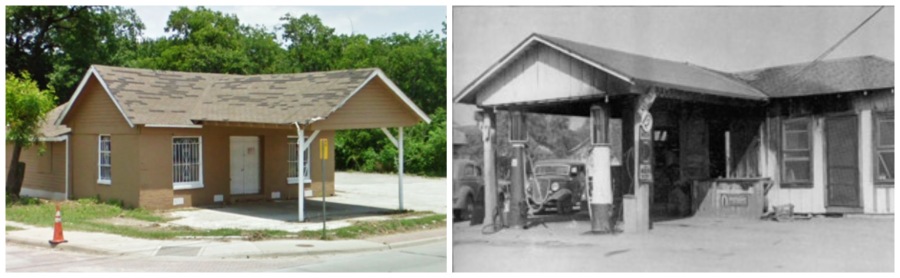

The property was the family home of Depression-era outlaw Clyde Barrow. Clyde’s parents relocated their house to this site in the 1930s and attached a filling station to the front of it. The family operated the gas station while living in the attached house. Clyde Barrow and other members of the Barrow Gang visited the residence often with their gang after he and Bonnie Parker, whom he met in 1930, became outlaws.

The story of Bonnie and Clyde fits into a time in American history during the first half of the Great Depression when there was an increase in the number of gangs traveling through the Midwestern states while stockpiling weapons and committing armed robbery and murder. Many of them were dead by 1935 thanks to a larger initiative by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to eradicate the Depression-era gangsters. Bonnie and Clyde were high on his list following the murder of officer Malcolm Davis at 3111 N. Winnetka Street and, in 1934, the pair was killed in a shootout with police. The media sensationalized stories about Bonnie and Clyde, and they became antiheroes for a general public who was reeling from the economic realities of the time and exhibiting a growing mistrust of government and public institutions.

Bonnie and Clyde came of age while living in West Dallas’ Cement City which, at the time, was one of the most economically disadvantaged areas of the city. While Barrow did hold several odd jobs around town, he chose a darker path and spent his late teens committing robberies and petty theft. West Dallas native Elsa Cadena said it best at yesterday’s Landmark Commission hearing when she noted that “West Dallas was where the poorest of the poor lived, the forgotten, the discarded, the immigrants and, yes, even the criminals.”

As with many historically disadvantaged areas, there are not many historical remnants of its past left, and much of it has been bulldozed to make way for new development. Former residents of Cement City and West Dallas are passionate about their history and saving what remains of it. The renovation of Eagle Ford School, now an official Dallas Landmark, was a turning point for West Dallas residents and an excellent example of how preservation can intersect with community building.

The initiation of 1221 Singleton began when Landmark learned that the property was sold and that owner Brent Jackson, president of Oaxaca Interests and developer of Sylvan Thirty, was considering demolition. Landmark rarely initiates properties over the objection of the owner, but it has happened in the past. Some examples include the Stanley Marcus home which was initiated by Landmark Commission after learning that the owner intended to demolish it. City Staff held several meetings with the owner to discuss the designation and to craft appropriate preservation criteria for the structure, and the owner became supportive of designation.

A similar story played out for Lakewood Theater and Bella Villa Apartment Building. Dallas High School, also known as Crozier Tech, is an example of a building that was designated by Landmark and sat empty for many years until the right owner came along and recognized the value in the building’s history and architecture. It is likely that none of these buildings would be standing today without Landmark intervention. In contrast, the Struck House at 1923 N. Edgefield is an example of a property that was initiated by Landmark, but the new owner remained opposed to the designation and, in the end, the Commission voted not to proceed with designation.

Landmark initiation does not mean that a property is a Dallas Landmark… yet. Initiation triggers a lengthier process that involves gathering further information about the property’s physical condition and history, writing drafts of the designation materials, and meetings with the owner to determine appropriate preservation criteria. Landmark then reviews all completed designation materials to make a final determination on the property’s eligibility as a Dallas Landmark and votes to either approve or deny the designation. The designation then must be approved by City Plan Commission and City Council before it officially becomes a new Landmark (view a full description of the steps to designate a structure as a Dallas Landmark here).

For better or worse, the story of Bonnie and Clyde is intrinsically linked to the greater overall history of West Dallas and the Great Depression. The site remains a very popular stop for visitors, tour groups, and others who seek to make sense of their violent crime spree. Part of the duties of the Landmark Commission is to identify properties that hold historic significance for Dallas residents. Because of the property’s association with significant person(s) as well as its association with national historical trends, Landmark determined that the property potentially qualifies for Landmark designation and elected to begin the initiation process.

By city ordinance, the initiation phase can last no longer than two years, but may end sooner depending on the circumstances. Stay tuned for further developments on the potential designation of 1221 Singleton!

Read the initiation letter for 1221 Singleton here.

NOTE: Landmark Commission opted to hold the initiation for 3111 N. Winnetka under advisement. This property is also associated with Bonnie and Clyde, and was the location where Officer Davis was killed by Clyde Barrow. The vote for the initiation of this building will occur at the April 6th Landmark Commission hearing. Read the initiation letter for 3111 N. Winnetka here.